Imperfectionism

The real psychology of dance

“Make it your own.”

I remember the day I figured out what that meant.

It’s what we’re supposed to do with ballet: learn the steps, get proficient at the technique, study other dancers’ performances, and then take ownership of it. But aren’t you automatically doing that just by doing it? Just by dancing those steps yourself? I mean, you must be the owner of the choreography when it’s your body performing it. There can’t be anyone else.

Yet for years, I was frustrated and confused by the oft-repeated directive to “make it my own.” I wanted specifics! Tell me what to do and then I’ll take that to the sky. Oh… wait…

The day of my revelation came when I was still a student, long ago in the middle of a summer intensive. One morning when I was in technique class, almost done with barre, we were doing a grand battement exercise. The pianist played something so rousing, majestic, thrilling that I felt this wave of power throughout my whole body, from fingertip to toe-tips, and I channeled it out through those grand battements— not just by kicking as high as I could, but by throwing my energy up and then controlling it on the way down, fitting myself right into that magnificent beat and melody, timing it out to become one (or so it seemed to me) with the pianist’s exact phrasing and accents. By calibrating my energy and not holding back. The structure was the combination (the specific arrangement of the exercise), but the grand battements themselves were mine.

The foundation was the way the teacher had designed the exercise— and then, I started to understand the infinite ways to actually do it.

I also realized that day (maybe not concretely, quite yet) that this was why there is no “ideal” or “perfect” in dance. For all of my and my teenage classmates’ envy of this dancer or that one, her feet or his jump or their solid pirouettes or that person’s figure or crystalline movement quality, our admiration was just that— an appreciation of other dancers’ qualities. With our adolescent emotion, we probably said to each other (and ourselves) that we yearned to be just like so-and-so. At that age, our excitement and motivation were exploding— and we were just beginning to wonder… “What possibilities do I have?”

I’m about make a statement that might be surprising, controversial, or sound plain wrong (or hypocritical coming from someone who wrote a book with the word “perfection” in its subtitle.) But stick with me and hear me out.

Dancers are not (necessarily) perfectionists.

I add the qualification because I can’t and won’t speak for every single dancer. There are some individuals who do have the extreme and paralyzing condition of a perfectionistic personality (and there has been much research and writing on the hazards of perfection-centric language, culture and cuing in ballet.) I know all too well how easy it is, especially in the ballet studio traditions of decades past, for a dancer to fall victim to overly negative thinking, self-destructive tendencies, or— especially— to lose sight of their love of and reasons for dancing.

But I don’t think those problems really stem from “perfectionism.”

Like many other stereotypes, the assumption that all dancers are obsessed with “perfection” rankles me. And from my years in the ballet profession, watching and knowing other dancers in the studio and theater, personally and professionally, I can say definitively that we’re not all perfectionists. In fact, we may be just the opposite.

I know why the “perfectionist” label can easily be stuck on us. But true perfectionists, as explained in this excellent piece in The New Yorker by Leslie Jamison, live life under a relentless self-imposed ban on being satisfied. It sounds awful to live like that— the people described in Leslie’s article simply cannot be happy with themselves, with others, or with the world as a whole. Everything falls short. Dancers, however, keep striving, pushing forward, questioning, challenging themselves (and yes, doubting themselves too)— but our effort isn’t in pursuit of some remote, never-attainable ideal. We love the work itself. We love to tinker, to troubleshoot, to fine-tune, to experiment and assess and play. We do it because the climb up a mountain is much more fun (and gratifying and interesting) than standing still at the top (paraphrased from Robert Redford, RIP.) For a dancer who doesn’t want their finite career to end, there’s emotional wisdom in savoring the climb beneath a peak that is forever hidden in the clouds.

Here’s what non-perfectionist dancers are:

Meticulous

Detail-oriented

Stubborn

Determined

Dogged

Committed

Passionate

Patient

Persnickety

In love with what they do

In love with the process of doing it

It’s the last two points that are why folks assume that dancers are perfectionists. They see us spending hours and hours, day after day after day, working our bottoms off going through the same basic, repetitive exercises at the barre— so we must be obsessed with something we’re not achieving— right? Non-dancers suspect that we’ve become crazed by an idealistic obsession (as we see in Black Swan and other portrayals of ballet in pop culture) and therefore will be eternally dissatisfied.

But, in fact, I think we’re actually afraid of perfection— or, at the very least, skeptical of it. Because, as my teacher Suzy Pilarre and others showed me, perfect is boring. In art, “perfect” is the antithesis of what we want. Greatness, meaning, beauty— yes. But a dancer lacking idiosyncrasies, individuality, “imperfections”? No.

When I was dancing full-time, what did I think about each day, if not perfection?

What did I go to the studio every morning in pursuit of?

Consistency? Yes.

Physical and technical strength? Yes.

Sensitive, nuanced artistry? Yes.

The mental and physical energy each morning to do a good solid class and get through a long rehearsal day? Yes.

Carrying that energy through the day, to keep up with my partners, my co-workers, the choreographer, the rehearsal director, and the artistic director? Yep.

Better padding for my soft corns? Yes!

Stamina to get through a really hard variation or pas de deux? Yes, please.

Being better than the day before? Hmm, not necessarily.

Being as good as the best I’ve been? Or as yesterday? Yes. That would be great.

Not getting injured or feeling a new ache or pain? Definitely.

Helping a choreographer bring their vision to life? Being an instrument in their creation? Absolutely. That feels amazing.

Roaring applause? Well, no… to be honest, by the time the applause starts, we just want to get our pointe shoes off and go home.

During my formative years at the School of American Ballet, the “right” way to dance was outlined in both specific and general senses: there were the details of technique (here’s how to hold your arms, here are the positions of the legs and feet, these are the names of these steps and here’s how to do them), but although that instruction was ongoing as we advanced, gained proficiency, and built from simple elements to complex ones, our teachers made it clear that what we were building was just the foundation.

The concept of a “right way to dance” meant applying these essential principles: energy, attack, phrasing, visual engagement, awareness and sensitivity to the dancers around you, the music (extremely important!) and projection of all those things as far and broadly as you could. I was lucky that, along with my fellow SAB students, I got to see New York City Ballet performances all the time. We were all drawn to different dancers in the company that we most loved watching. I realize now that what I found so magnetic about my own top faves were their specific traits— it was their uniqueness that I found so indescribably beautiful. I couldn’t take my eyes off the footwork of one NYCB dancer without “perfectly” arched feet because of the way she used them. I was mesmerized by the different movement qualities that dancers with wildly varying silhouettes created. It made me curious about how I could move, with my own energies and contours, without straying from the clearly defined combinations I was given in class the next day. And that led to my grand battement revelation that hot, sticky, summer afternoon.

So, there was never any “perfect” or “ideal” way to perform or to be. Instead, there was a perpetual process of shaping, re-imagining, enjoying, exploring, and repeating, with every single iteration different— maybe only slightly, but different— from the last.

One of my teachers, the wonderful Francis Patrelle, said at the start of nearly every class, “Redefine your tendu every day.”

And he was so, so right. He was reminding us that ballet is a process that never ends. No matter how advanced you are, how many years you have been a professional, how many roles you’ve performed or rave reviews you’ve gotten, your tendu will be different tomorrow morning at the barre. So you’ll take some deep breaths, go back to the most basic of basics, and redefine. You’ll not have to start from scratch— your muscles don’t lose everything overnight— but sometimes it feels that way.

Which leads back to why dancers are not perfectionists.

We do obsess over details, get frustrated when we can’t execute a step the way we want to (or the way we did yesterday), stubbornly practice a turn or partnering maneuver dozens of times in one rehearsal, painstakingly fine-tune the specifics of choreography. But I’d say our work habits are more fixated on getting things “just right,” not being some sort of generic “perfect.” That’s why we’re nit-picky about the precise line of our arms, angle of our heads, curve of our fingers and placement of our feet. Maybe we’re “just-right-ists.”

We dancers also know when to stop (again, contrary to what some of the sensationalistic movies or TV shows would have you believe). We love to admire another dancer’s work and pause to cheer for a gorgeous balance, fabulous pirouette, crazy fast footwork, or a performance (in studio or onstage) so raw with emotion that the applause builds from stunned silence to a roar.

When I was dancing professionally, I relished in the fatigue at the end of each day. I could go home and sleep even if I hadn’t been “perfect” that day— which was every day. When you know that the point of everything is the process, you can let go of any one disappointment or frustration or perceived unmet goal. A lot of dancers will tell you, when asked what they love most about being a dancer, that their favorite thing is to rehearse, not to perform.

We know— and love— that there’s no end (now that’s freedom!) There are multiple little “ends”— a performance’s final curtain, the end of a rehearsal hour, a dead pair of pointe shoes, and the obvious finality of a farewell performance— but to dance means a daily renewal. We cherish the process, not the goal. There is no goal. The goal is to keep going.

And that is why the word “perfection” is in my book’s subtitle. The perfection is the life. The perfection is the continuum. It’s the totality of all that goes into the beautifully endless redefinition of my tendu.

“What is that sticky substance that pulls us deeper and deeper into this world of dance? The further we explore the peaks and valleys, forests and oceans of the dance world, the more lost we become. The pathway ahead gets smoother and yet more twisty and hilly the longer we follow it, and the end of the road will never appear.”

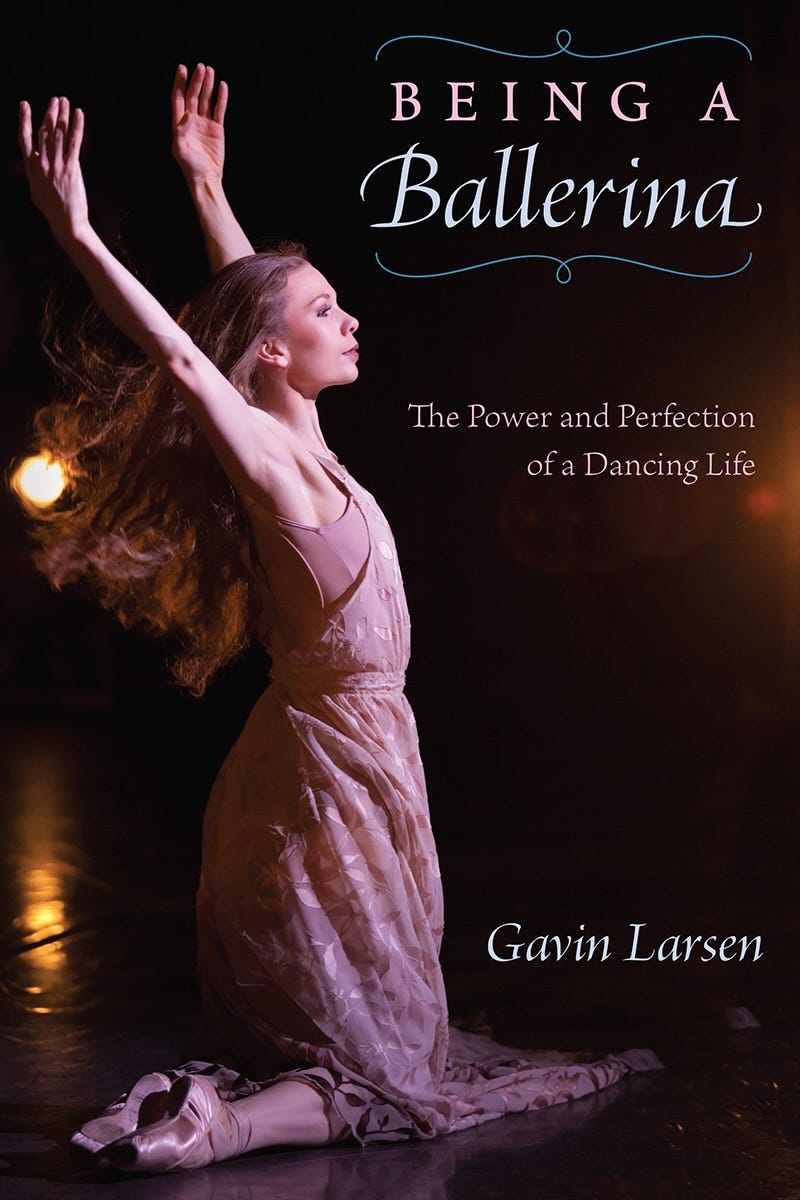

Being a Ballerina: The Power and Perfection of a Dancing Life

The mother of one of my students told her daughter (who was devoted to ballet), “You’re the hardest-working lazy person I know.” I think what she meant was that she saw in her daughter was a strange juxtaposition of intensity and reluctance that she found hard to understand. The intensity is in the moment— diving headfirst into the work at hand— and the reluctance is actually an acceptance that there’s no reason to relentlessly race around the track. Because there’s no finish line and no competitors. There’s just now.

When I teach, I do urge my students to fixate. I try my hardest to make them try their hardest. They catch on to my enthusiasm and go along with my insistence as they find themselves getting a little stronger, a little straighter, and little higher, faster, slower, more controlled, more powerful, a little better at the details of ballet every week. They’re finding their own pathway, though for now, the youngest ones don’t look much beyond this year’s Nutcracker performances. I see my older students, though, having revelations like my own. They’re taking my combinations and making them theirs.

It’s not about getting to “perfect.” It’s about getting to just right.

“In art, “perfect” is the antithesis of what we want.”

Nothing has resonated so well!! Thank you for your beautiful, and insightful words 💓💓

Excellent thoughts. Loved the pictures of your past partners at OBT, too!